Nationally recognized artist Robert Singleton, 86, has been a

full-time practicing artist and painter for over 65 years.

He moved to the mountains of West Virginia in 1978

in search of privacy, time, and space.

He designed and built his home and studio and has since

called a remote mountain top home.

Ambient Music by Dan Morro

These galleries are best viewed with

full screen on a Mac, PC or Tablet

turn on sound

The galleries will open on a phone however, such devices

will not provide the visitor with the full quality

of the galleries or art work.

GUEST BOOK

Index of Individual Virtual Galleries

* West Virginia 2012 ~ 2023

Gallery VII

Romanced Horizons

* West Virginia 1978 ~ 2023

Gallery V

Quest For Grace

Gallery VI

Quest For Grace II

* Screamer Mountain – 1973 ~ 1978

Gallery III Mystical Meditations

Gallery IV

Hard Edge Pastels

* Florida - 1963 ~ 1974

Gallery I

Finding A Way

Gallery II

Diverse Works

* Virginia - 1949 ~ 1963

Gallery 01

A Beginning

The Works of Robert Singleton

Life's Connected Events . . .

Now,

that

I

am

in

my

85th

year,

I

can

only

look

at

my

previous

work

as

a

preamble.

I

work

daily,

exploring,

discovering

new

inspirations

for

new

images.

Knowing

the

vastness

of

the unknown becomes ever clearer.

The

lifelong

story

of

my

artistic

approach

is

to

question

creativity

itself

and

where

it

comes

from.

Is

it

really

about

the

artist/creator

as

the

author

of

metaphors;

the

biographer

of

illusions?

Or,

is

it

more

about

life

and

the

influence

of

life's

connected

events

which result in the measured evolution of the imaginative act?

In

the

mid-1950's

I

studied

painting

under

a

professor

who

was

a

disciple

of

Hans

Hoffman.

In

the

sixty

some

years

since,

my

art

has

passed

through

many

transformations.

In

the

same

way

I,

as

a

person,

have

evolved.

Life

and

Art,

the

two

are

still analogous paths; side by side, my work has always reflected these many passages.

One

of

the

journeys

of

great

impact

in

my

artistic

development

took

place

in

1960.

As

a

young

adult,

I

traveled

across

the

United

States

and

saw

for

the

first

time

the

great

expanse of the plains of the Midwest.

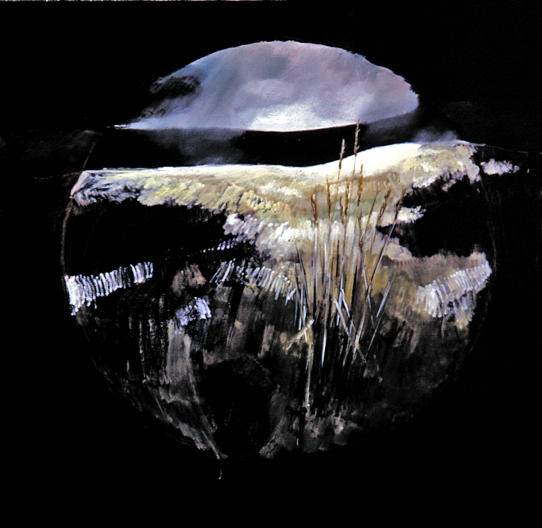

Visually

what

I

experienced

was

profound.

The

Horizon

Line.

I

wrote

in

my

sketchbook,

"You

can

turn

360

degrees

and

see

nothing.”

From

Kansas

on,

this

line

spellbound

me.

A

line

that

was

the

division

between

sky

and

the

wide-open

prairie;

uncluttered space, empty space with this hard, crisp line intersecting.

Continue to Next Page

As

a

child,

on

many

levels,

I

was

accustomed

to

loneliness.

Visually,

what

I

witnessed

translated

to

deep

emotions.

I

saw

what

I

as

a

child

had

felt.

I

found

in

the

natural

world

a

human

emotion.

In

the

years

to

come,

this

emotion

would

translate

into

images

of

empty

space

divided

by

a

single

horizontal

line.

The

tie

between

the

visual

and

the

emotional

self

would merge.

Creativity

has

been

a

voice

expressing

a

deep

personal

desire

to

speak

of

the

broad

spectrum of human emotions. Our state of existence . . .

The

creative

process,

as

often

as

not,

is

cluttered

with

human

frailties.

Still,

art

is

a

subjective

manifestation

of

those

frailties,

an

expression

of

both

the

pain

and

the

joy

of

life.

The pain of the internal search and the joy of the found.... expressed!

The

one

absolute

truth

of

my

life

has

been

my

art,

a

visual

communication

of

poetic

perception,

a

reflective

state

of

an

authentic

search.

At

a

given

moment

in

time

that

creative

expression

becomes

a

composite

of

the

entirety

of

this

person’s

being

.

.

.

bringing

all

the

creator is to that discipline.

In

the

mid-1970s

looking

up

towards

the

sky

my

imagination

was

captured

again,

this

time

by

clouds.

Images

we

often

take

for

granted,

seen

every

day;

above

the

horizon

line

filled with abstract forms of light and atmosphere, the ever-changing poetry of clouds.

Creation

is

often

described

as

a

movement

from

an

eternal

unformed

and

unchanging

dark

chaos.

Sky

and

earth

lie

together

in

a

changeless

embrace

until

forced

apart

by

their

offspring,

who

drive

a

wedge

between

them

producing

light

and

movement.

My

paintings

explore

these

creation

dynamics.

Why

did

our

early

ancestors

pick

the

meeting

of

sky

and

earth as a creative beginning?

Each

of

my

later

paintings

is

a

creation

whose

subject

is

creation.

Sky

and

earth

are

usually

male

and

female

in

myth

and

from

this

polarity

all

other

things

derive.

Without

polar

tensions

there

is

no

motion

and

no

story.

Thus,

the

sky

and

sea/earth

are

always

divided

by

a

horizon-wedge

keeping

them

in

tension

and

producing

clouds,

which,

in

their

movement

and

reflection

of

light,

bring

temporality

and

process.

Nothing

changes

more

quickly

than

clouds,

whose

shape

and

color

can

announce

brutal

violence

or

reflect

glorious

spectacular

light through which our consciousness seeks to gain unity with nature.

While

every

work

of

art

has

to

achieve

a

balance

of

the

tension

or

forces

that

motivated

it,

my

paintings

include

a

sense

of

imminent

future

which

is

full

of

potentialities.

Most

of

my

clouds

announce

better

and

maybe

greater

events

are

about

to

happen. The paintings reveal the "world" of our moment in a more relevant way.

Why continue this quest? The answer is not complicated. My art is my Life.

Creatively I see the future of my work/life as a continuation of providing a means of

uncovering the core of our collective evolutionary message; our intuitive understanding

and cumulative experience ingrained and transmitted through generations since the

dawn of time. Creativity is the search for our shared universal awareness.

HOUSE IN THE CLOUDS: The Artistic Life of Robert Singleton

R e s o u r c e s

•

The Art of Living: 60 Propositions on Becoming

•

The Cloud Painter and the Berlin Musician

•

CORE of MY JOY / Memoir

•

Until I Become Light

Award winning film documentary aired on PBS

2002 Produced by Real Earth Productions

•

West Virginia Public Broadcasting | By Kyle Vass

Published September 1, 2021 at 12:01 PM EDT

•

The Works of Robert Singleton

1949 ~ 2022

A Matter of Conscience

GUEST BOOK

BACK TO GALLERIES

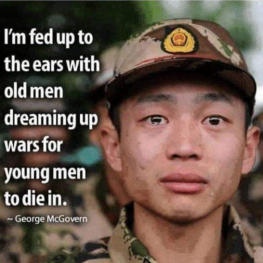

“War is a place where young people who don’t know each other, and don’t hate each other, kill each

other, by the decision of older rulers who know each other and hate each other, but don’t kill each

other…”

Erich Hartmann: German fighter pilot during World War II.

*

March 24, 2022: I saw this picture in the news. It collided with me at the core. Bring back images from the distant past.

*

1969 Vietnam

2022 Ukraine

Next Page

Casualties of Wars

Romance on Canvas

By Grace Kehrer

Spring 1969

Robert Singleton as an artist stands in the shadows of Romantic, realistic and transcendental

movements where notions like Nature, Man, Society, Individualism and Responsibility are strained

though the reality of two world wars, police actions, a crass materialism and an intensifying

depersonalization. Finding himself caught up in a miasmic atmosphere created, in part, by computer,

"Wagers" and a relativistic viewpoint, Singleton, the self-admitted incurable romantic, attempts to

understand a sick society and bring intelligible order to a chaotic universe.

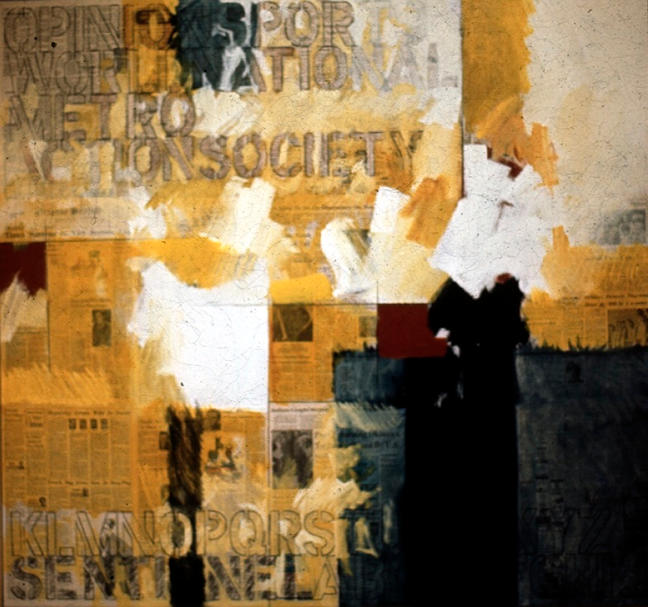

Singleton's paintings on oversize canvases, done in primary colors, stand testimonial to contemporary

styling techniques executed under the banner of "Art for Art's sake." However, the questions, often

spelled out in block letters, are timeless and universal. While Singleton does not offer a solution to the

problem of man's inhumanity to man, nor locate a center of human spirituality, he does examine the

phenomena, continuing the quest in a personal, thoughtful and sensitive manner.

The second painting develops the idea of journalistic responsibility and influence. Interjecting often ignored,

possibly forgotten notions of equality, ethics, freedom and unbiased news, printed upon a white field

surrounding a patriotically colored centre, one can only hope these subtleties are not lost on the Sentinel staff.

Journalistic Responsibility – 1967 – 78” X 120” ~ Commissioned by the Orlando Sentinel

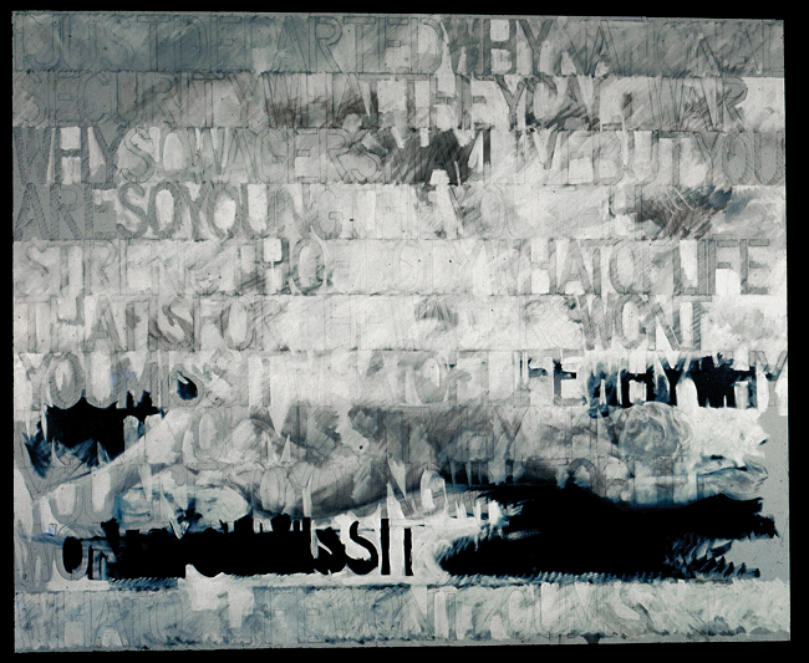

Singleton's latest work, one produced after much thought, recognizes the reality of the generation gap.

A literary message, in dialogue form over the figure of a dying boy, it exposes the inarticulate nature of

questions, the naivete of answers and the pain suffered by men separated by chronological age and

appetite.

Text as it appearers in painting

IJUSTDEPARTEDWHYNATIONAL

SECURITYWHATTHEYCALLWAR

WHYSOWAGERSMAYLIVEBUTYOU

ARESOYOUNGTHEYOUTHHAVETHE

STRENGTHOFBODYWHATOSLIFE

THATISFORTHEWAGERSWONT

YOUMISSITWHATOFLIFEWHY

WHATOFLIFEWHYWONTYOU

MISSITWHYWHYWHYWHY

Legible

"I just departed." "Why'?" "National

Security; what they call war."

"Why?" "So wagers may live" "But you

are so young" "The youth have the

strength of body" "What of life?"

"That is for the wagers." "Won’t

you miss It?" "What of life?''

"Why?" "Won't you miss it?"

"Why?" "What of life?''

1969 Florida State University

– With WHY? hanging the background; students discussing the responsibility of artist according

to what they believe is morally right, to document their time, to protest, to reflect through their work the contemporary

violent values of humanity and the world. Be it visual arts, literature or music.

GENESIS: Excerpt from book, Core of My Joy

FLORIDA 1965 - 1973

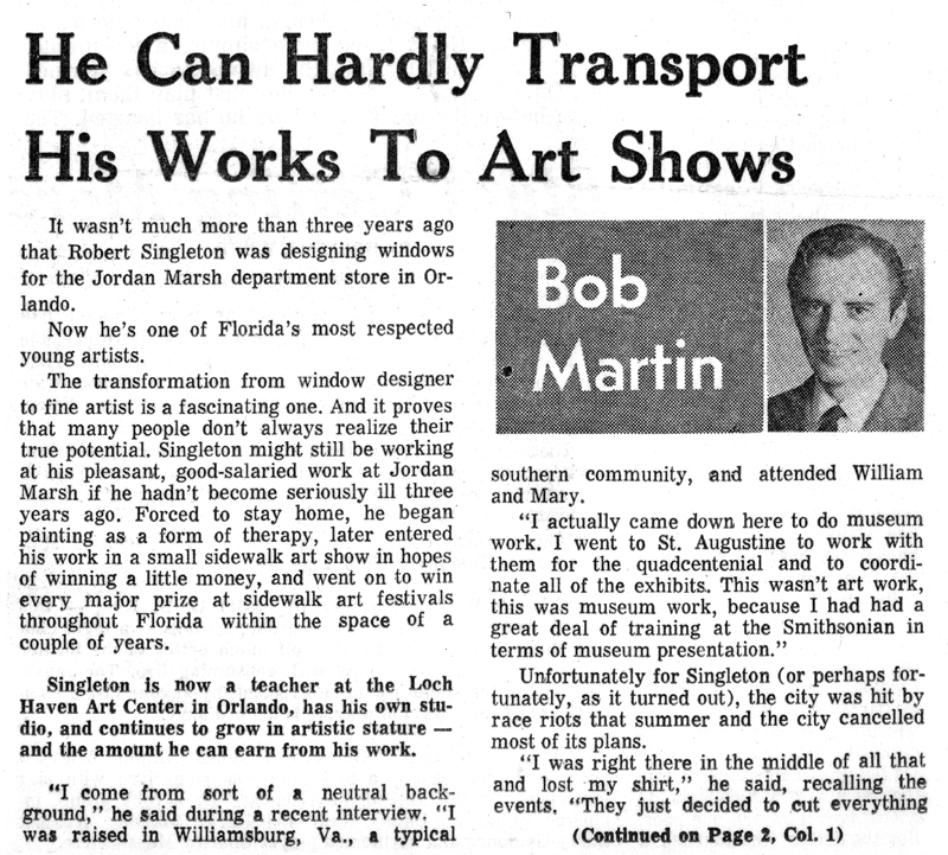

I returned to Orlando, Florida, and my position with Jordan Marsh. I was good at

my work and they were happy to have me back. I found an apartment in Winter

Park, a community near Orlando.

Because of my skills as an artist, the director of the display department soon put

this ability to use. The men and women’s fashion windows were changed

monthly. Each of these display windows had 8 foot by 18 -foot background panel.

Each time, I would paint a thematic scene on ten of these panels.

These display windows became quite popular, as each of the background panels

were original painting. Over a period of time, they were saved and reused. It was

not fine art, but I was working and very happy with my $50.00 a week salary.

Several months after my return, I discovered a small cottage for rent north of

Orlando, in the tiny community of Altamonte Springs. This cottage was perfect,

located on an acre of land, surrounded by great spreading oak trees. The owner

told me no one had lived in it for a number of years. If I chose to rent the cottage,

it would be on an as-is basis, for $50.00 a month. It had so much character, built

of old brick, with a very large fireplace and screened-in porch on the back, a real

fixer-upper. I saw all kinds of potential and happily agreed to rent the cottage.

Within the first year, I cleaned, painted, landscaped, and furnished it. This

wonderful little house was more than a place to live. It gave me a sense of

stability and roots. It was my home. As a result, I was stable, working, and paying

the bills. My life was on an even keel. The fates were indeed being good to me.

Except, there was one thing missing. I was not painting. I had not put brush to

canvas since I left St. Augustine, the year before.

It seems the fates had other plans for me. I became physically ill, a full-blown

case of mononucleosis. I could not go to work. The doctor instructed me to have

lots of bed rest, and at work, they thought I might be contagious. Weeks went by

as I began to improve. I was bored. In order to help pass the time, I pulled out my

paint box and on the back porch, began to paint. There was no pressure. I even

wondered if I still had that creative drive. Well, I did paint again. Within a short

time, I had produced five or six canvases. Most were my remembrances /

impressions of Conk Island and the dunes.

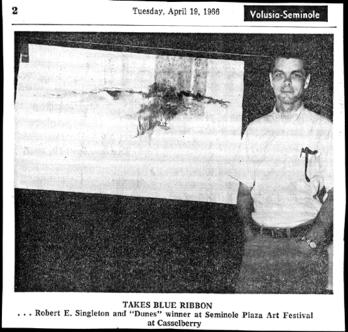

As a result of not being able to return to work at Jordan Marsh, my cash flow was

running short. Coincidentally, I had been told that in a few days there was going

to be an art show/competition held just a few blocks away from my home at a

small shopping mall. This clothes line art show was open to anyone who showed

up.

I had never submitted my work to a competition or ever entered an art show of

this nature. I just thought maybe peddling a painting or two would help the

financial situation.

I strung a heavy wire between two poles and hung the paintings like hanging out

the wash. All I had to do was sit and wait; hopefully someone would purchase a

painting. I did wander around looking at all the other artists’ works that were on

display.

My paintings by comparison, appeared to be very different, almost abstract to the

very realistic work of the other artists. I thought, “I must have an odd way of

painting, of seeing my visual world.” I did not feel encouraged. There were lots of

lookers, but none were interested in purchasing my work. By afternoon, the

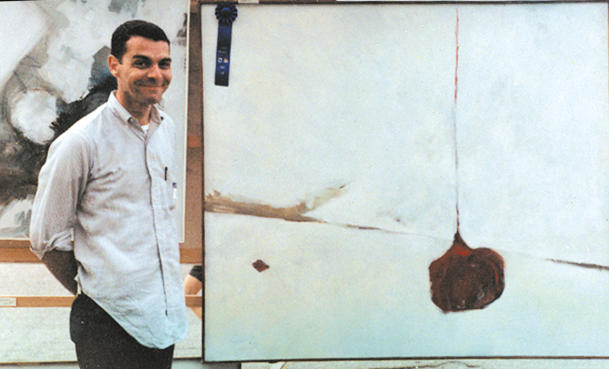

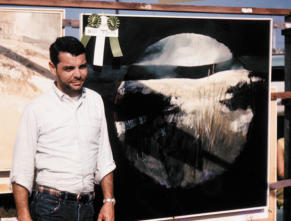

judging was to take place. There were three awards, with a blue ribbon and a gold

pin for best in show. I won! --- A painting entitled “Dunes I” won Best in

Show. There was much excitement as all the other artists came over to

congratulate me.

The next day I sold a painting for $30.00. In addition, a number of the artists

present told me there were many sidewalk art shows of this nature all over the

east coast of Florida, almost one or two monthly. They persuaded me to enter

these other shows. And so, I did. The following weekend at the Daytona Beach

sidewalk art festival, I sold three paintings.

The next weekend at the New Smyrna Beach sidewalk art festival, “Dunes

II” won first prize, another blue ribbon and one hundred dollars cash.

I found myself faced with having to make a decision that could potentially affect

the rest of my life. I was now well enough to return to the stability and security of

a $50.00 dollar a week paycheck. “Don’t rock the boat. You are stable and doing

just fine with your job at Jordan Marsh. Your painting should be just a hobby. Be a

Sunday painter.

Would it be an irresponsible act on my part to quit my job and become a full-time

artist? Even now, as I describe that moment in time, I feel the anxiety, the

insecurity of not knowing. To follow the dictates of my heart and take a chance,

to invite the lack of security into my life.

The choice was made. A definition given, a commitment to explore beyond my

human boundaries, to take chances, to become vulnerable. In time this choice

would be the instrument that would lead to exposing the very image of my soul.

My identity was found both internally and externally. It was a beginning, a fresh

start in life.

From April 19, 1965, when my painting won that first award, my art career

escalated at a rate almost beyond belief. These sidewalk art shows were for many

aspiring artists, an important means to have one’s artwork exposed to the public,

museum curators and commercial gallery owners. Gallery owners used these art

shows as a means to find artists, who they would in turn invite to become

members of their galleries stable of artists.

On June 17, 1966, just three short months after winning that initial award, the

first public showing of my work through a commercial gallery opened. Webb

Gallery was a new and provocative gallery handling all the major artists from the

entire state of Florida. This one-person show was the first significant endorsement

of the work. For me a validation of its worthiness. In all honesty I was humbled

and honored to have my work hanging with such an auspicious stable of

artists. The exhibition was even reviewed by the art critic with the Orlando

Sentinel. With the headline, “He’s best when he’s different. July 10th, 1966,

another one-person show opened with another gallery, this exhibition established

the begin of an association with the Salty Dag Art Gallery in Cocoa Beach and its

owner, Kit Young. Kit became a close personal friend and in time became my

agent. From the very beginning she believed in my work and me, always

encouraging, coaxing and advocating both professionally and personally. If I were

to credit one person for nourishing the establishment of my career, it is Kit. Kit

came to my studio once a month. I would show her all the new works.

She would make a number of selections, take the new paintings back to her

gallery and immediately put them on display. There seemed to be an enormous

interest in my work growing in the Cape Canaveral space coast region. Generally,

by her next visit, all the paintings she had picked up the previous month had been

sold. After several of these visits, Kit suggested that she would be willing to

purchase all the monthly works from me outright. What this did mean for me? I

did not have to wait for the works to be sold before I would be paid; it became

the security of a steady monthly income. November 5th, 1966, encouraged by Kit,

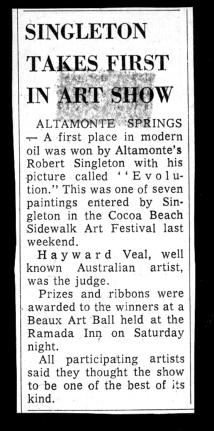

I entered one of the major art shows for the state of Florida, the Cocoa Beach Art

Festival. One of the paintings entitled “Evolution” won first prize.

The list of shows and awards would grow. In just four years, my works won 22

major awards, including 12 best of shows. In just one show, the 1968 Daytona

Beach Art Festival, the work won two first-place, a second, Judges Choice and two

honorable mentions. Every painting I had on display won an award.

The judges for these art shows were exemplary. They ranged from nationally

recognized museum directors to curators and critics. Including Dr. Lester Cook, [at

the time the curator of American painting at the Smithsonian Institutes’ National

Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.]. On three separate occasions Dr. Cook gave

my work the highest award. Apparently, Dr. Cook felt the work was strong. “I am

very impressed with Robert Singleton’s work. He is obviously a mature, serious,

and a sensitive artist.” Dr. Cook also wanted to help further my career by making

a number of opportunities available to me. On one occasion, on behalf of the

United States State Department, he invited me to go to Vietnam as an artist war

correspondent. I thanked him for the offer, but refused.

Winning all these awards was certainly a boost for my self-esteem. However,

what were most significant were the caliber of the judges and their endorsement

of my work by selecting it for the top awards. Listed below a few of the judge’s

statements which appeared either in the press or in personal letters to me:

James Johnson Sweeney, former director, Guggenheim Museum, Museum of

Modern Art, and The Houston Museum of Fine Arts. “Knowledgeable, competent

and sensitive, also extremely assured in its handling.”

Dr. David W. Scott, Director of Fine Arts of the Smithsonian Institute, Washington,

D.C. “I was impressed by his breadth and largeness of concept, and by the

combination of control and vigor. The works conveying a sense of authority, which

made them outstanding.”

August C. Freundlich, Director, Joe and Emily Lowe Art Gallery, University of

Miami, Miami Florida. “I personally find his work fresh and exciting, and worthy of

serious consideration. I look forward to hearing more from this artist.”

Bartlett H. Hayes, Jr., former Director, Addison Gallery of American Art. “I find in

his work, an abstract feeling for nature itself as we understand it in our present

century. Its quality seems so obvious that it hardly needs words to fortify it.”

Cleve K. Scarborough, Director, Mint Museum of Art. “Mr. Robert Singleton

recently had three prints accepted into the Mint Museum’s annual Piedmont

Graphics Competition. Two of the prints received purchase awards. The prints

were extremely unique, especially in technique. The subtle modulation of the ink

on the metallic-like surface was a most unusual effect. The abstract forms seemed

to float without the existence of a ground. We were very anxious to have one of

Mr. Singleton’s prints in our permanent collection.”

As my work became more widely known, it seemed opportunities were coming at

me right and left. I was deeply flattered, but many I could not accept. For

example, the Dean of the Art School of the University of Hawaii invited me, with

all expenses paid plus salary, to the University campus as Artist in Residence for

an indefinite period. NASA, along with a number of nationally known artists,

invited me to come to Cape Kennedy to witness the launches of the Apollo moon

missions. Though I did not attend I did witness the Apollo 17-night launch by the

invitation of the Mayor of Orlando as part of Vice President Spiro Agnew’s party.

I was nominated and awarded a Ford Foundation Grant to attend the Tamarind

Institute in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Tamarind had been established to

encourage or assist recognized artists in the creation of lithographs.

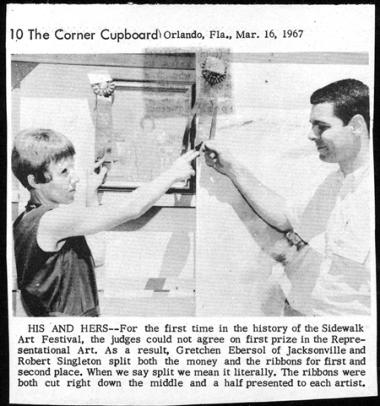

In March of 1967, and the two following years, I entered my work in perhaps the

largest and most prestigious art show in the Southeastern United States, the

Winter Park Sidewalk Art Festival, Winter Park, Florida. This show represented

five to six hundred, preselected, artists from the entire country. Over a period of

three days, three hundred thousand of the art-loving public would attend this

show. In 1967, a painting entitled “Double Entendre” won the First and Second

awards in painting. This special award resulted from the two judges refusing to

concede on their choice for First Place. As a compromise, First and Second Place

was combined, this was split between another artist and myself.

As with many artists, I began to explore other creative mediums of expression. In

my case, I started working in sculpture and printmaking. In 1968, at the Winter

Park show, I won best of show in graphics. In 1969, I won best of show in

sculpture.

I recall jokingly saying I had a Michelangelo syndrome. I was being recognized for

sculpture and print making, when my passion was in my painting. Michelangelo’s

passion was sculpture, but he was forced to make a living painting ceilings.

Suddenly, there was always food on the table. As Kit would say, metaphorically, “I

went from flour pancakes to smoked oysters.” This was such a long way from

painting in that room in the Seattle YMCA, a long way from that starving artist

eating peanuts and Coca-Colas and hustling his wares in bars.

It is time to slow down and backtrack. My career had taken off like a rocket. Also,

within that first year, 1966, I started teaching with the Lock Haven Art

Center. Within just a few years, I was teaching almost full time, as many as three,

three-hour studio classes daily. Teaching beginning drawing, painting to master

critique classes. There was always a waiting list of students wanting to attend

these classes. Sometime in the early 70’s when the art center went through a

significant remodeling and expansion, the Lock Haven Art Center became the

Orlando Museum of Fine Arts, a major museum and art school.

One of my other skills was happily put to use, that of exhibit designer. On the

occasion of the gala grand opening of the new museum, I designed and installed

all the new exhibitions. I continued to design and install all the major exhibitions

throughout my tenure with the museum.

Fortunately, adjacent to my little cottage was a small two-room building. A retired

doctor had constructed this building as a woodworking hobby shop. As the doctor

became too old to pursue his hobby, all the tools were sold and the building

emptied. This was the state in which I found it, when I first rented my home. I

contacted the doctor’s wife and she agreed to let me rent the building. My first

studio! What a luxury, a space devoted exclusively to my work. I later purchased

this building and created, between the cottage and studio, a walled-in courtyard.

What was I producing in this studio? I was very prolific. Every single image created

on either canvas or paper originated from my imagination. On very few occasions

have I used my photography as a reference. The subject matter of these early

paintings was almost exclusively of nature and my memory of it, that is, in generic

terms, land and seascapes. The specific images were my many remembered

impressions of Conk Island and of course of that Midwest horizon line. As in

music many times the works were themes and variations. I now feel it was not

just that I was so prolific, but foremost, I was constantly searching, pushing and

exploring my creating boundaries, always reaching beyond, growing beyond the

previous painting.

From 1966 to 1970, through this constant searching, the work passed through a

major metamorphosis. It was a transformation from impressionistic studies of

nature to very large canvases which were totally nonobjective (no recognizable

subject)

At the end of 1970 I made an important decision, I stopped entering all art

competitions, side walk art shows etc. This decision was based on competitive

presser. I, my work, had an unbroken record of winning the top awards. It was

uncanny what happened. Because of my “perfect score,” I was told, that when a

number of artists made application to enter these competitions, they would want

to know if “Singleton” was going to be in the show. If the answer were to the

affirmative, they would say, “Why bother?” and not enter. This both embarrassed

me and put more undue pressure on me. There was a second reason, which I

recall expressing the following way, “It was like being the fastest gun in the west

sooner or later someone was going to shoot me down.” And so, I quit while I was

ahead. As soon as the word circulated around that I was no longer participating

and competing, I was invited back as a juror.

Awards – Honors

2021 -22 ~ Tamarack Foundation for the Arts, Master Artist Fellow, Lifetime

Achievement Award.

2018 ~ George Mason University

“Where it comes from: An exploration of human creativity”

Guest lecturer for the 2018 “Vernon and Marguerite Gras Lecture in the Humanities.”

1986 ~ Benefit Exhibition “Robert Singleton Weekend” –

Guest of honor at black tie dinner and exhibition of new works. Donated twenty-nine

works to raise funds for the Maitland Art Center’s building fund. The event rose over

$20,000 for the art center. Gallery talk and lecture at the Maitland Civic Center.

Maitland, Florida.

1985 - 1995 - Served on the Board of Directors of the Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

Center.

1977 ~ Endorsement of influential art dealer / artist agent Leo Castelli.

1970, 71, 73 MacDowell Fallow Grant, MacDowell Colony, Peterborough, New

Hampshire.

1973 ~ Received invitation to be Visiting Artist and Instructor – University of Hawaii –

(Did not accept)

1970 - 1971 ~ Piedmont Graphics Competition Mint Museum, Charlotte, North

Carolina, Juried group graphics show. Two purchase awards.

1970 ~ Ford Foundation Grant to attend Tamarind Institute,

College of Fine Arts at the University of New Mexico. (Did not attend)

1969 ~ Winter Park Sidewalk Art Festival, Best in Show, Sculpture, Award of Merit,

Painting – Winter Park, Florida.

1969 ~ Ocala Art Festival, Best in Show - Ocala, Florida.

1968 ~ Winter Park Sidewalk Art Festival, Best in Show Graphics, Winter Park,

Florida.

1968 ~ Daytona Beach Art Festival, First Place (oil painting), First Place (non-

objective)

Second Place (representation), Judge’s Choice (special award)

1967 ~ Florida Seaside Art Show, First place in painting. Indialantic, Florida.

1967 ~ Cocoa Beach Art Festival, Beat in Show in painting, Cocoa Beach, Florida.

1967 ~ M & C East Art Show, First Place in painting purchase award, Ocala, Florida.

1967 ~ Winter Park Sidewalk Art Festival, First and Second place in painting. Winter

Park, Florida.

1966 ~ Cocoa Beach Art Festival, First Place in painting, Cocoa Beach, Florida.

Toxic Methyl Bromide a health hazard

Essay by Hardy Ghost

"There they are. You can see the white spots on their heads and tails." Robert

Singleton points at the pale blue sky. A pair of Bald Eagles are circling between

his house and the next ridge north of him, about half a mile away. They came

back sometime during the last 20 years, he says. The majestic bird of prey has

been the national symbol of the United States for a long time. Once on the

verge of extinction because of pesticide use and hunting, its numbers have

increased, and the population seems stable and thriving again. They have also

found a home near Robert’s house, nestled in the forest of the Allegheny

mountains in Eastern Hardy County, WV. “We also have Golden Eagles, lots of

Wild Turkey, Black Bear, Raccoons, Opossums, and I even saw a Bobcat in my

front yard a year ago or so.” In this area, wildlife is thriving, there are springs and

creeks with clean water, and now in spring, with the forest waking up from

winter, the air is filled with scents of new life. An idyllic place away from noise

and pollution, a landscape that has not been touched by industry,

overpopulation, or climate change, nature’s refuge.

Singleton, a landscape painter who is nationally acclaimed, moved here 45 years

ago to escape the fast lane of life and find peace, live in nature, and clean air.

Since then, many more people have discovered the beauty of this place. They

have built cabins and homes in these woods, many of whom have moved here

permanently. Several National forests and protected areas in Eastern Hardy

County attract hikers, mountain bikers, kayakers, and nature lovers. Hunters,

out of the area and local alike, appreciate the richness of these woods flush with

deer and fill their freezers with game during the season. Organic farming has

been emerging in nearby Wardensville, where local youth learn to grow food,

treat land and soil with respect, as well business skills. But there is trouble

brewing in paradise.

On the next ridge, less than a mile northwest of Singleton’s residence, located at

Park Farm Drive between Baker and Moorefield, the company Allegheny Wood

Products International Inc. is planning to open a wood fumigation facility on the

grounds of an old poultry farm, which may be issued a permit by the Division of

Air Quality (DAQ) to emit up to 9.54 tons of Methyl Bromide per year as

determined by a preliminary evaluation.

Methyl Bromide, also known as Bromomethane, is a toxic, hazardous, ozone-

damaging gas that has been banned in most countries of the world and also

neighboring states like Maryland. It is strictly regulated and being phased out in

Virginia and North Carolina. The gas can harm human health, including

neurological, reproductive, respiratory, kidney, liver, and esophageal damage

and nasal lesions. While close proximity contact is the most dangerous, low-

dose exposure over longer periods can be harmful. Little to no regulation exists

regarding the protection of residents and the general public from the toxin in

ambient air, so of course, an Air Quality permit notice in the Moorefield paper

can state rightfully that “all State and Federal air quality requirements will be

met […]” because there are little to none. When you try and find more

information about it, the most puzzling fact may be that Methyl Bromide was to

be phased out completely in the US in 2017, “so why will we have to worry about

possibly inhaling it in a pristine natural environment like the one we live in

here?” asks a resident living close by. Furthermore, the toxin is subject to the

Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA), a federal law

designed to inform communities about planning efforts involving potential

chemical hazards on the state or local level.

Neighbor Neil Gillies, whose homestead is about a mile and a half from the

proposed facility, would like to know, “How in the world did an industrial facility

that will emit significant quantities of an extremely toxic gas go under the radar

and get to the point of receiving a provisional permit? Why have there been no

public hearings about this?” Pete Osinga “moved here for the clean air and

might have made a mistake.” His new house is less than half a mile to the

southeast of the site, and he may bear the brunt of chronic low-dose exposure

since winds mostly come out of the west and northwest and may carry

Bromomethane released by the company onto his property. Other folks from

the larger Hardy community want to turn up at the next Planning Commission

meeting and object to this development. Still, there is also a feeling of being

powerless among some. One neighbor with a property adjacent to the site

shrugs his shoulders in despair. “Williams, the owner of this land, also sits on

the Planning Commission. You know how this county works.”

Indeed, when digging a little deeper, one can find articles about a huge Poultry

farm near Old Fields, WV, about 2 years back, having received permits against

the protest of local people and without the knowledge of the then President of

the County Commission, who “had no clue that there was even an application

submitted or approved.” The owner of the land for the proposed fumigation

facility turns out to be the same entity, having pushed for and now running a

Mega Poultry farm in this county. Back then, Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable

Future had sent the new Hardy County Planning Commission president a letter

pointing out risks. “We believe that expanding poultry operations in Hardy

County will create similar hazards as those observed on the Eastern Shore of

Maryland, marked by an increase of contaminants and risks to soil, air, ground,

and surface water quality and the health of Hardy County residents.”

There is a pattern emerging. The health of residents and the environment does

not seem to matter versus the mighty dollar, where there is little regulation and

oversight in rural areas. Local opponents of proposed projects that threaten to

endanger their well-being have no choice but to step into the ring against a

Goliath out of their weight class. How do you win a fight like that when the other

side is that well-organized and can seemingly bend the rules to their will?

Will landscape painter Robert Singleton have to resort to painting toxic clouds?

Will the Bald Eagle in this area survive Methyl Bromide, a chemical used in

pesticides for farming back in the day, after recovering? Will the indifference of

cold business practice win over the value of public health and nature still

unspoiled? There is also concern about the effects on livestock, with a small

poultry operation less than a mile from the fumigation site. Dennis Funk has his

cattle grazing just a few 100 feet over on a neighboring property throughout the

season. Will someone inform him about the potential hazard looming? Last but

not least, property values may drop in the immediate surroundings because

who would want to potentially buy a home and property with the outlook of

having hazardous gas dispersed over their heads?

Baltimore Harbor had an average amount of 26 to 37 tons of uncontrolled

annual emissions of Methyl Bromide before fumigation for export reasons

ended in the port around 2016, and the use phased out in the state of

Maryland. In comparison, that would mean that local neighbors, residents,

wildlife, and the environment may soon be subjected to the toxic emissions of

roughly a third of a Baltimore international port near Baker, WV.

“For now, all we can do is get organized and find out when the next Hardy

County planning meeting takes place and turn up in numbers!” Sue Ryan, who

lives in the county and would like to see air quality and the environment

preserved, is trying to stay positive and mentions how we can still write

representatives, start petitions and try to make our voices heard.

Right now, any resident can write a short letter of concern and send it by May

5

th

, 2023, to:

Steven R. Pursley, PE

WV Department of Environmental Protection

Division of Air Quality

601 57

th

Street, SE

Charleston, WV, 25304

If public interest is expressed significantly, a meeting will have to be held. This

arguably should be the case in any way due to the federal law of the Emergency

Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act. But as this written piece has been

trying to show, Hardy County, WV, seems to be off the beaten path in location

and when it comes to rules and regulations. Residents must be motivated to

speak up and participate in protests to keep Hardy County’s air clean.

Written by: Hardy Ghost

Links:

https://civileats.com/2021/04/07/a-huge-new-chicken-cafo-in-west-

virginia-has-stoked-community-resistance/

https://ncnewsline.com/briefs/thousands-of-people-live-near-log-fumigation-

operations-royal-pest-solutions-fined-for-methyl-bromide-emissions-violations/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Bromomethane

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emergency_Planning_and_Co

mmunity_Right-to-Know_Act

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v

=B3jEoLO-yVk